Full description not available

A**Y

A great read.

Heitner has chosen a fascinating subject, and she what we learn about Black produced television really gives us an interesting look at the 60s and 70s, at the corner of media and race.Very cool!

S**A

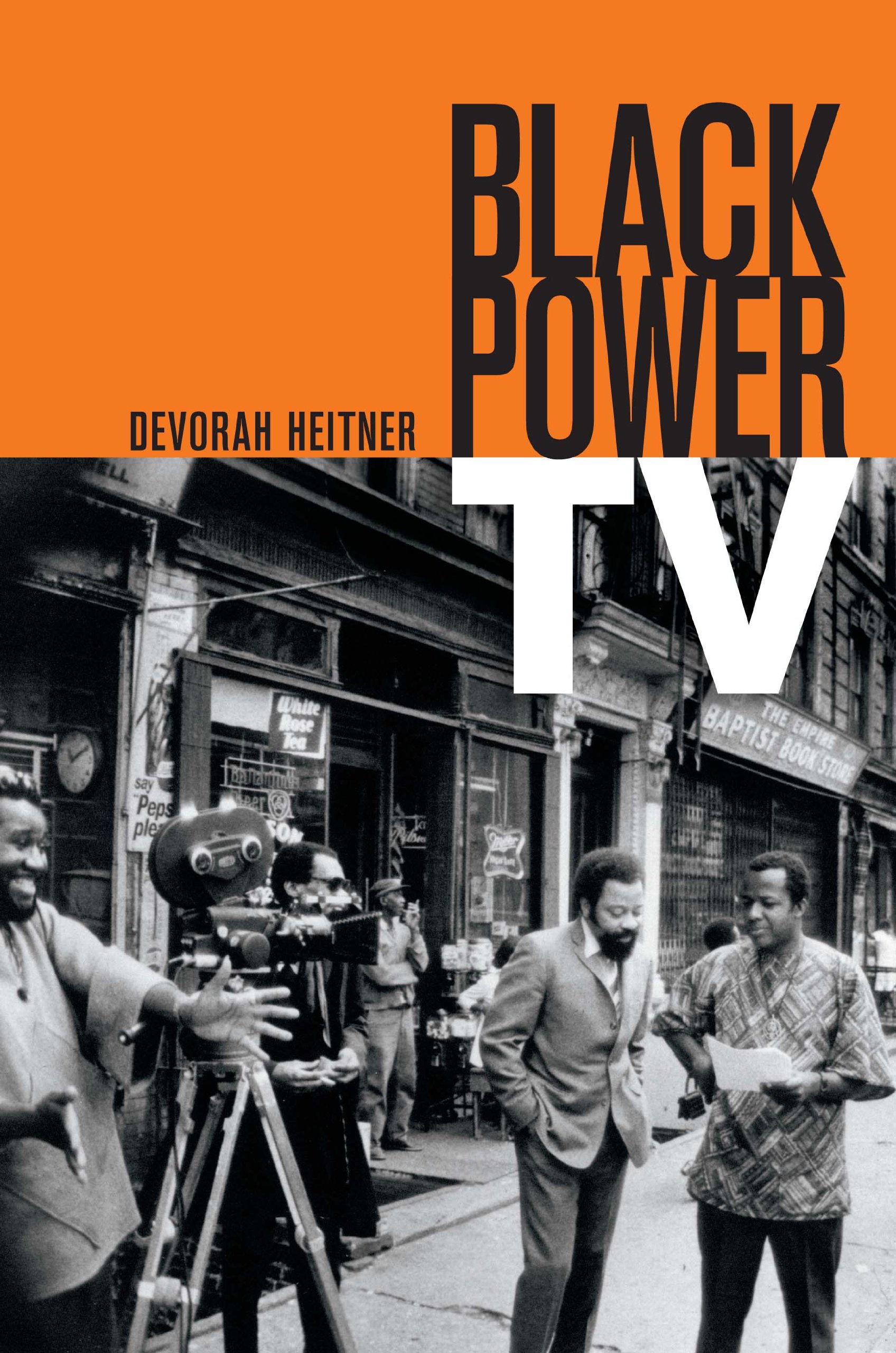

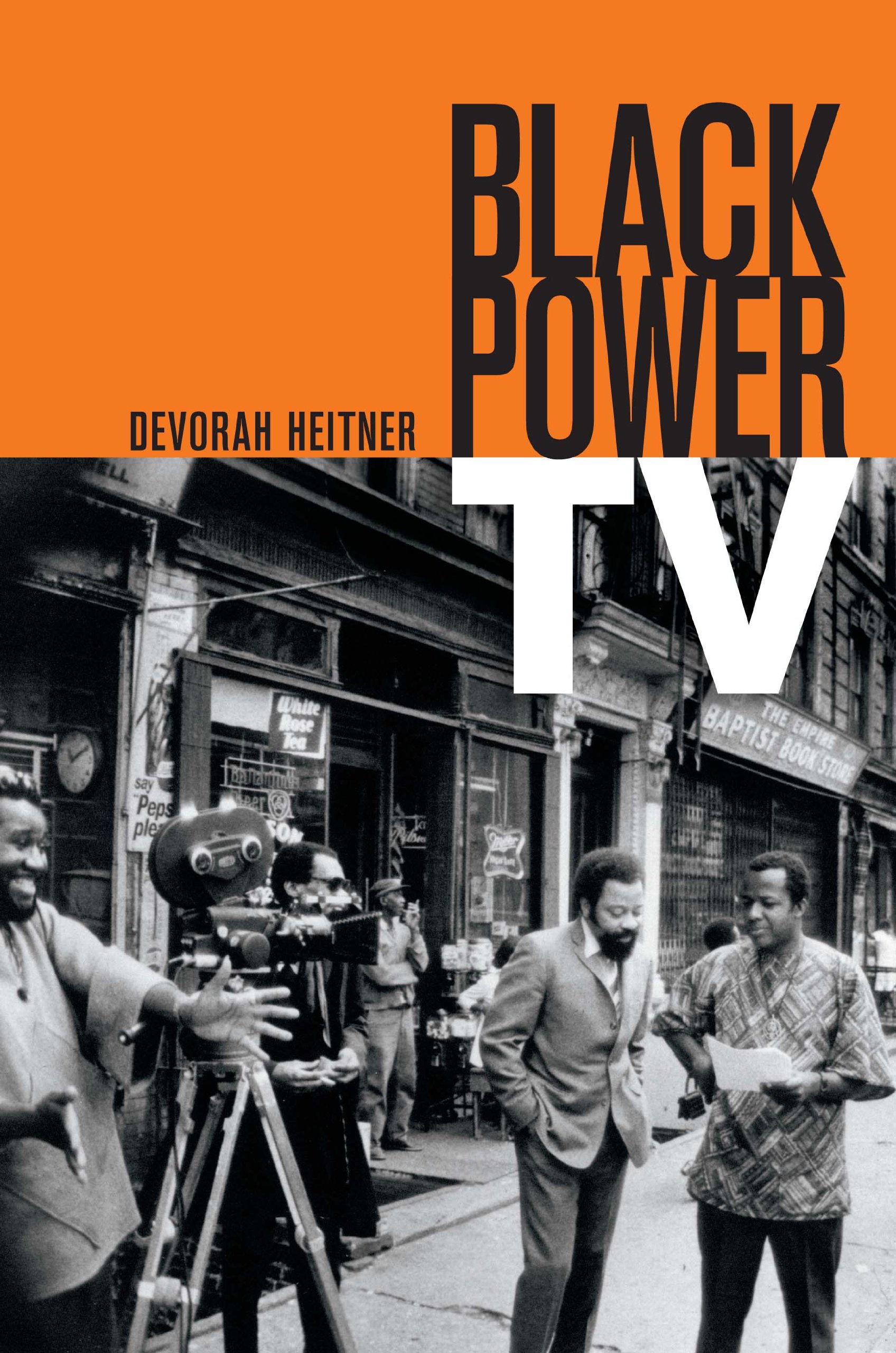

Black Power TV

Devorah Heitner’s Black Power TV (2013) examines the historical, political, and cultural emergence of Black public-affairs television programming in the United States during the era of Black Power (roughly from 1965 to 1974 as it is given in the purview of her analysis). Heitner’s (2013) thesis is that the genesis of inclusionary efforts made by White media gatekeepers and their ilk in the aftermath of Martin Luther King, Junior’s assassination led to the creation and marketing of Black critical perspectives in the mainstream televisual sphere. In an effort to contain increasingly volatile resistance among Blacks and out of remorse for King’s murder, stations broadcast the funeral nationwide. Amid a social atmosphere rife with fear, distrust, anxiety, frustration and hopelessness, as Devorah Heitner (2013) contends, political and media power brokers sought to leverage mass media access against a nationwide torrent of Black outrage and a government mandate to foster and disseminate more progressive, balanced narratives of life within the Black community. The transmission of King’s funeral not only demonstrated significant ratings among audiences but also significant power to defuse and re-orient undesirable modes of popular/grassroots systemic engagement. If the stark juxtapositioning of King’s solemn, orderly, reverential send-off against the unfolding discordant fury and fatality visually confronted and engaged White audiences, it certainly transfixed and mollified significant numbers within Black audiences. Moreover, as Heitner (2013) points out, the report issued by the Kerner Commission, assigned to examine the nature of Black rioting and resistance, scathingly noted that the media’s narrowly constructed coverage, lack of context, feeble framing of issues affecting the Black community, and racially biased exclusion of—and abject insensitivity to—Black perspectives were largely influential factors contributing to civil unrest among Black people across the nation. The most famous line from the Kerner Commission’s report eloquently captures the sense of urgency, racial volatility and dangerous polarity of the time: “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal (Heitner 2013, p. 6).” The media landscape of the time reflected the Jim Crow status quo in its rhetoric, representation, and discourse: racialized, violent, pathological derogatory stereotypes that depicted caricatures of Black reality. King’s assassination and the Kerner report’s recommendations spurred a hastily begrudged reallocation of resources to foster media initiatives designed to include Black perspectives in the mainstream U. S. critical discourse. An amalgam of public and private funding (largely derived from the Ford Foundation) spawned a new genre of public-affairs programming, with a decidedly Black emphasis.Black Power TV (2013) analyzes the ways in which Black media makers exerted a transformative influence through their pragmatic renegotiation of the content, aesthetic, and production values of programming while simultaneously renegotiating the terms under which the Black community engaged a largely hostile (when not apathetic) entrenched power-elite structure. Given that the ominous sense of a Black revolt loomed like the sword of Damocles in the minds of Whites in general and the power-elites in particular, media leadership grudgingly conceded the reigns of editorial and creative control to Black producers and editors, but never fully relinquished suspicion of genuinely viable Black programming. It is in this tenous atmosphere that one sees the best of Devorah Heitner’s analysis of the intersectionalities that converge to form strategically nebulous and, at times, subversive power-plays in the televisual sphere of the media landscape. She deftly frames her inquiry and assessment of the power relations in a mixture of Critical-Cultural, Marxian, Gramscian, Feminist and various other theoretical strains relating to the rhetoric, representation, and discourse of power and how the exertion of that power permutates as it traverses the public sphere.

B**S

Concise, bad ass and fun

I adored reading this. Anyone interested in media studies, African American film and television during the late 60s should take a peek at this stellar read ;)

Trustpilot

2 months ago

2 days ago